Most people that know me know that I'm a big fan of tabletop RPGs! Here are some reflections of my experience running a large scale Dungeons & Dragons Westmarches campaign for around 30 players over the past 2 years.

My previous experience with D&D

I was introduced to tabletop RPGs through D&D 4th Edition in 2011, where I learned how to be a dungeon master through running a long form campaign along with a few one shots. I fully got into the hobby in 2015 with D&D 5th Edition, motivated in part by Stranger Things and Matt Colville, who introduced me to Critical Role.

When running tabletop RPGs, I mostly take on the role of the dungeon master where I have run 5 different long form campaigns in D&D (as well as many one shot sessions), both in the same physical space as well over digital tabletops. I’ve even run a simplified version of Dungeon & Dragons in an hour for over 120 people! Games at my table tend to be medium to high fantasy, using lots of homebrew or third party material, and tonally not too serious but not too wacky.

I have since branched out into playing other tabletop roleplaying games, and have also dabbled with writing D&D adventures and supplements as well as creating my own microRPGs.

Introduction: how did I start running Westmarches?

After speaking to a few colleagues at the office, I knew there was some interest in playing D&D. While my original thought was to run a standard D&D game for about 6 people, I also expected that more people might be interested in joining than is normally manageable in a game, especially after we started playing and word got around. This felt like the perfect opportunity to run a Westmarches campaign!

What are the Westmarches?

The Westmarches are a style of play first popularised by Ben Robbins (who has created well known tabletop RPGs such as Microscope and Kingdom). You can read more information on his site, but in short:

- Sandbox campaign: A Westmarches campaign tends to be more of an open world environment with an unexplored world to discover, and primarily focuses on exploration of the unknown wilderness. Players start in a small town that serves as their home base and are encouraged to venture out and explore. This doesn’t necessarily mean that areas will be level appropriate for players!

- No regular party: Players come up with their own sessions (”I want to explore this dungeon”, or “I want to save the princess in the tower”, or “I want to go north and explore”), and then recruit party members. This means party composition frequently changes, and there’s no fixed day or time to have a game. This also means that players are not tightly bound to the game; they can play as little or as often as they like, and new players are welcome to join whenever they like!

- Each session is self-contained: While in regular D&D games, it’s common to end the session and just pick up where you left off. In a Westmarches, since party compositions may change between sessions, it is assumed that all players return to base camp at the end of the session.

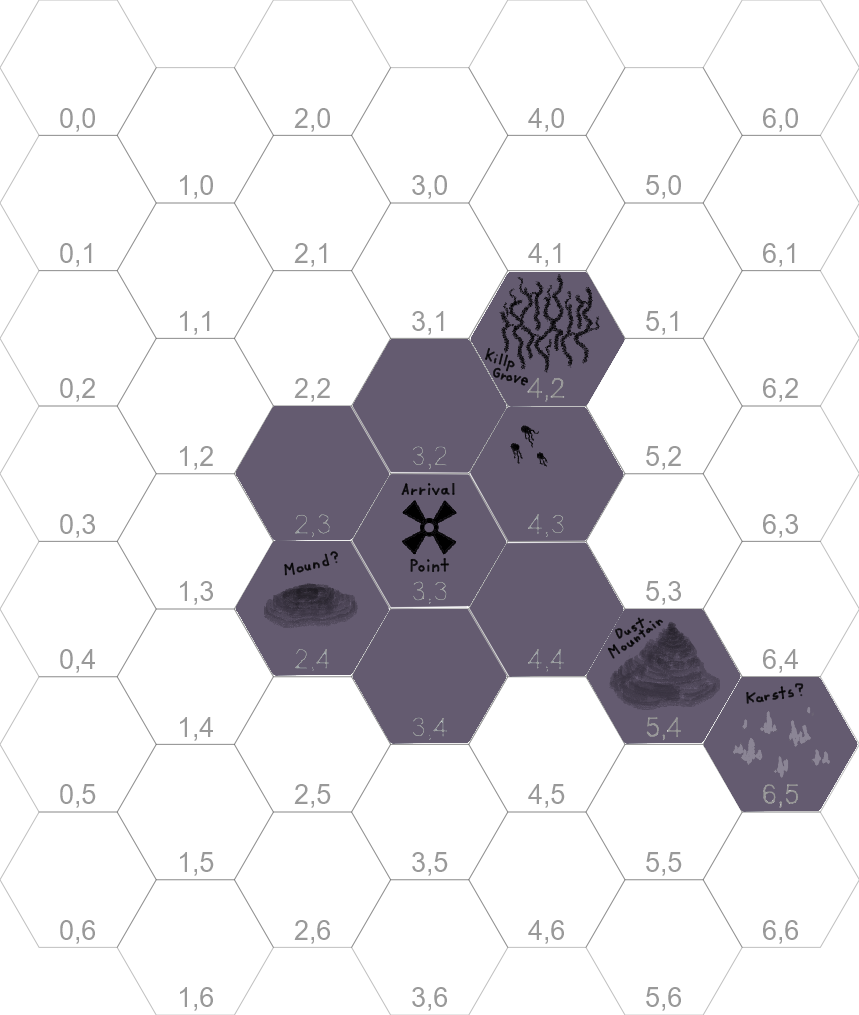

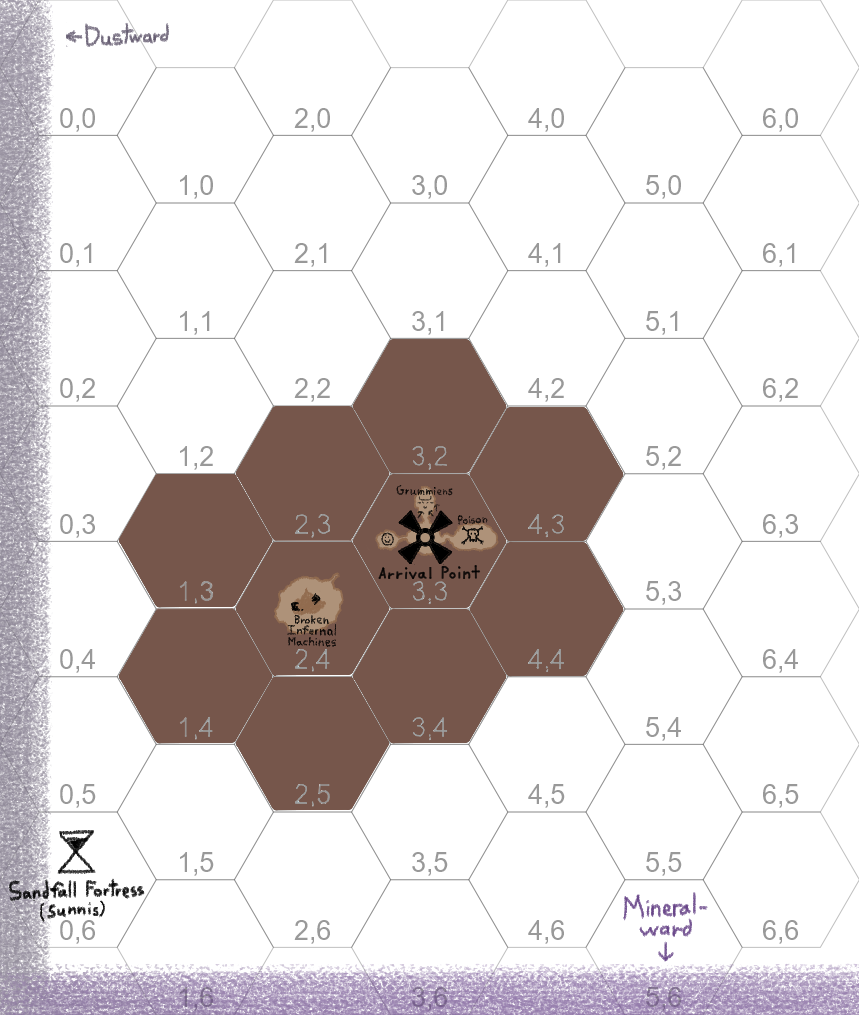

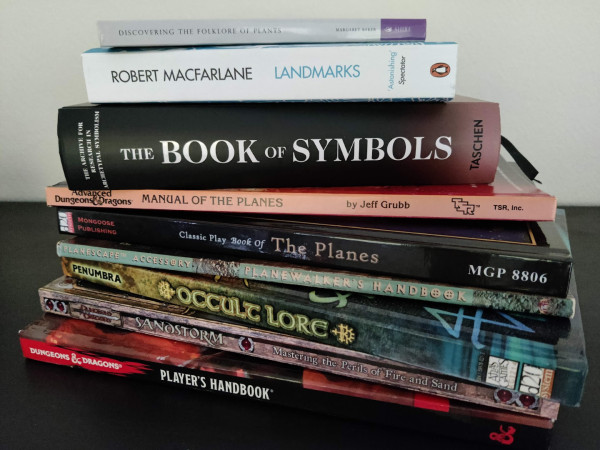

- Player driven: An empty shared map is updated by players based on their explorations, which future parties can use in their own sessions. After every session, players are expected to write a short summary of their adventure, as well as update the shared map, to let future adventurers know what happened in the previous session as well as provide better context on where they could go next. Any errors made by players when making the map (such as by getting lost or being provided with vague or indirect directions) may result in future parties getting lost!

My initial prep

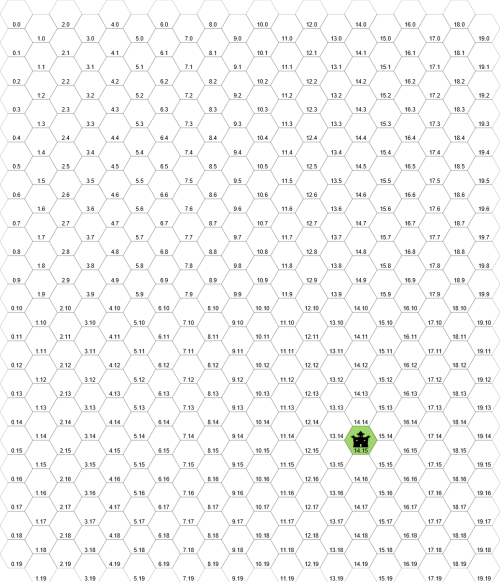

I first generated a 20x20 hexgrid map of the world using a free copy of Worldographer, tweaking the result slightly to allow for some variety in player adventurers. I then created an empty version of that map, revealing only the tile that players would start from.

I then starting writing up some introductory text that interested players could read to give them more info about my style of game, what the Westmarches style of play was like, how to join the game, how to participate, and my expectations at the table. I also prepped safety tools; namely Lines and Veils, where players could anonymously report which topics they did not want to appear in sessions, and X, N, and O cards to be used during play. For more information about appropriate safety tools during play, take a look at the TTRPG Safety Toolkit, curated by Kienna Shaw and Lauren Bryant-Monk.

I kept an updated list of the player roster, so that players could know who was playing, what characters they were running, and what levels they were.

Players could create a level 1 character using any of the official material released by Wizards of the Coast, with third party material accepted on a case by case basic. Evil characters were not allowed, and players were requested to pick non-evil deities from the Dawn War pantheon if they were needed.

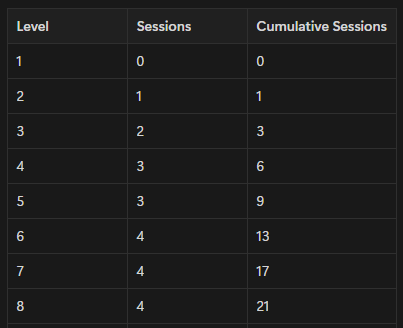

Since I decided to use milestone levelling rather than handing out experience points, I set up a reference table that I could use to see how many sessions a player would need to play in order to level up their character. I preferred milestone levelling since I didn’t want to have to complicate bookkeeping with so many players.

I wrote up a few rumours so that players could begin going on adventures and exploring the map; enough to get started for the first couple of sessions.

Finally, I announced that we were ready to begin in the channel I had created on the company’s Slack.

How I ran the game

From a practical perspective, I ran 3-4 hour long sessions after work for a party of between 4-6 people. At the beginning of every session, if there were any new players to D&D, I’d give them a quick summary of what they could expect and how the game was played. I also assumed that they hadn't read the introduction document and spent some time explaining my approach to running games and my use of safety tools. I also gave a quick description of the campaign's planar theme, as well as a summary of the Westmarches format if a player in the party had not played in the campaign before, regardless of if they were familiar with D&D.

Depending on the amount of time players would have given me before a session, I would always strive to prepare enough material for the time we had, and prepare a little extra in advance just in case players explored surrounding areas. For first time players, I tried to make sure that sessions contained both some roleplaying as well as a combat encounter in order to give them the most complete D&D experience possible.

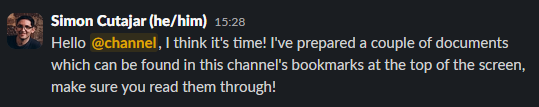

When preparing for a session, I tend to make use of any material from D&D 5th Edition that I have available to me, whether official, third-party, or homebrew. I also look at relevant sourcebooks from other editions of D&D (including third-party D20 material if needed), and sometimes takes inspiration from other TTRPGs and nonfiction books completely outside of the hobby. I don't tend to consult these while in a session; the only book I actively carry with me to games is the Player's Handbook. This is mostly because I have a lot of books, and they're very heavy to carry around, so I tend to prepare as much as needed from beforehand.

I make heavy use of Notion while running a session, since that’s where I keep most of my campaign and session prep. I also keep notes on NPCs that players have encountered, as well as magic items that they either own or have yet to find. I tend to stick to particular naming themes for NPCs depending on their species, class, and background, though I haven’t yet written these guidelines down. While previously I tended to have a table of entries for each hex on the map, in practice I found this to be unwieldy and not scale so well when I had lots of hexes prepared. Instead, I switched to using a tool called Kanka, mostly for its ability to pin metadata onto maps. This meant I could easily see where the players currently were and which hexes they were heading to, and simply open the one with the correct name.

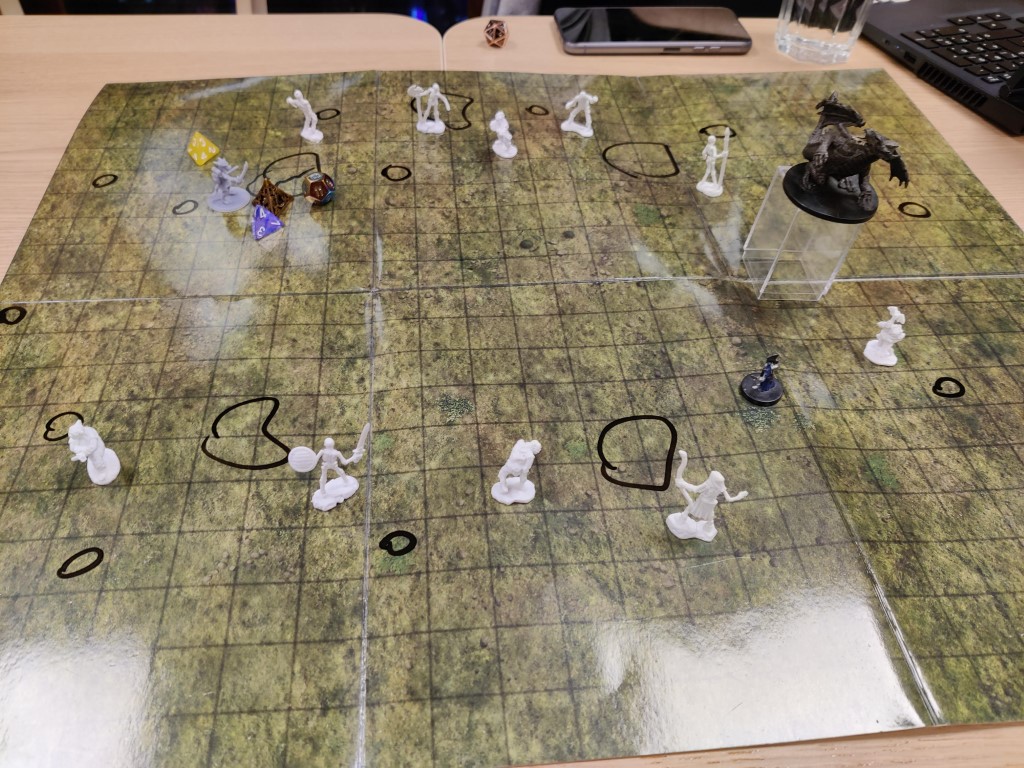

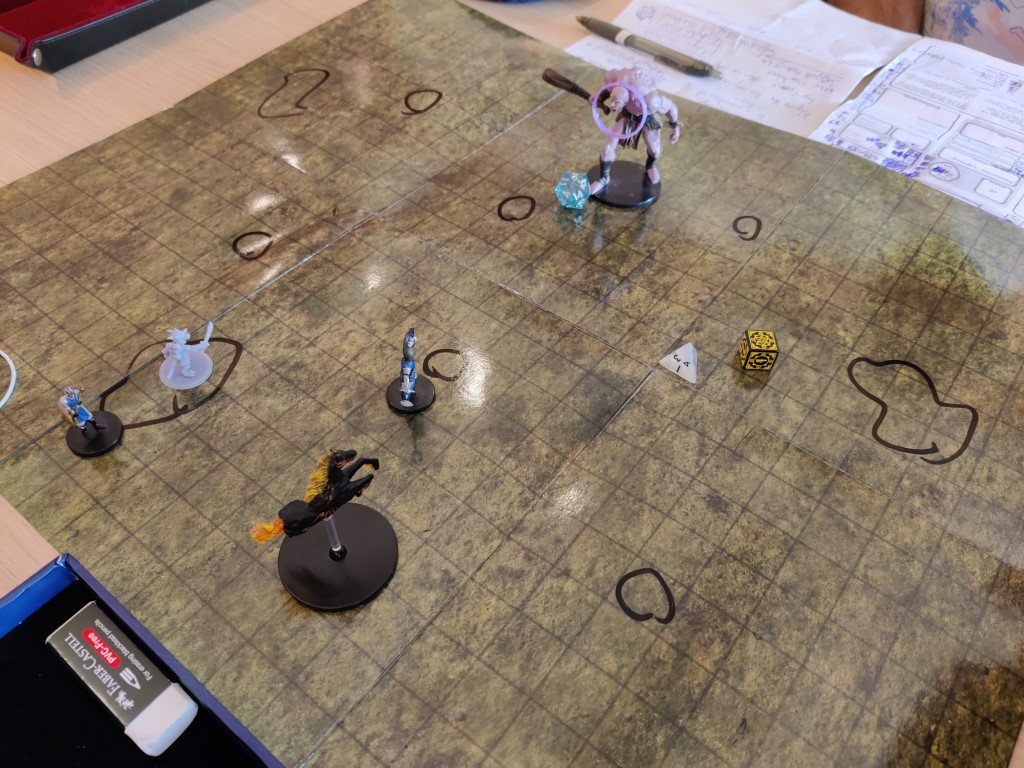

For combat encounters, I use a variety of miniatures that I've collected over the years on top of a few Pathfinder battlemats. Since I almost never have the correct mini for the monster or character that I’m portraying, I try to pick figures that either get close enough or are the right size. As soon as combat starts, I use a marker to draw significant terrain onto the battlemap I’m using, which can be erased afterwards. I normally mark any characters or enemies that have some sort of status effect or condition that is worth remembering with plastic coloured rings taken from soft drink bottles.

While running the game, I make use of pre-prepared music playlists that fit specific moods or locations (such as Forest, Tension, Battle, Underground, Royal, or Plane of Fire), which I control from my laptop. I’m always on the lookout for instrumental music that I think could be added to these playlists! I trigger this manually by switching playlists in VLC; I unfortunately haven’t found a good setup for this where I can crossfade between playlists with minimal effort. I don’t tend to use soundboards or similar programs such as Syrinscape; mostly because switching music is already quite fiddly and I also need to concentrate on running the game. All music is played through a portable Bluetooth speaker.

I don't tend to use a DM screen (mostly because I don't own one), but tend to roll dice behind my laptop. Depending on the stakes, I may sometimes roll openly in front of players, and may sometimes even ask players to roll for enemies.

After a Westmarches session is over, I encourage people to contribute to the map and write up session notes, which I would collect and compile to better help players plan for future sessions. While initially I would reward players that did so with DM inspiration, in practice I found that players tend to either not use it or confuse it with bardic inspiration, so I shifted to rewarding players with gold instead.

Learnings

Here’s a few learnings that I’ve taken away from running a D&D Westmarches campaign for 2 years!

Playing with Colleagues

Quite a few players in the campaign had never played D&D (or any tabletop RPG) before. They went on to become core players in the campaign, and even started exploring other tabletop RPGs such as Microscope and Lancer. I’m quite proud of having successfully introduced roleplaying to so many different new players!

As existing players talked about their adventures over lunch and speculating on what could happen next, other colleagues overheard the conversations and became interested in participating. This meant the player pool grew organically, allowing for variety in adventuring parties. It also meant that people got to interact with colleagues that they may not interact with during their day to day at work.

The downside of running everything after work at the office is that anything happening at work also affected game scheduling. This included everything from upcoming game releases or last minute bug fixed, as well as company layoffs (which killed the mood for a couple of months) or people leaving the company willingly. Long periods of summer and Christmas vacations also temporarily brought the campaign to a standstill.

Though I prefer playing RPGs in person and I generally stuck to that when running the Westmarches campaign, there were a few sessions with hybrid play (where some people also joined online), as well as one session that was fully online. I don’t think the hybrid play session was optimal, mainly due to the limitations of equipment; players couldn’t easily see the battlemat during combat, it wasn’t as easy for them to participate in conversations, and they were more likely to be interrupted or cut off in conversation. The fully online session worked better; while I’ve run an entire campaign in Foundry before, I used Roll20 for this session since it was only meant to be a one off. Players joined a voice chat over Discord and followed the session there, with combat and die rolls taking place within Roll20. The only downside to this setup was the lack of music, and while a solution could have been found, in practice I’ve found that having music in an online session alongside voice tends to confuse things.

Using Discord

While I initially organised everything in the company Slack channel, I decided to move everything to a private Discord server and personal Google Drive folder shared with players in order to better accommodate players who had left the company, as well as partners or spouses who were also interested in playing.

Moving to a Discord server also allowed me to better organise how the campaign was run; rather than post everything into a singular channel with some posts at risk of being missed, I could instead set up different channels and players could set up threads when they wanted to form a party. Discord also allowed me to set up hidden channels, which I also made use of.

Populating the Map

While I had generated a map with predefined terrain, I hadn’t yet planned out every encounter for every tile on the map. Not having a preprepared map meant I could populate these tiles with encounters that I thought were interesting, or that would help players progress further in their goals.

The downside of course, is that I spent a lot of time figuring out how to fill out the map instead of preparing for sessions. Certain tiles were improvised because I was caught off guard and didn't have anything prepared for that particular tile and I was desperately scrambling to find something interesting, while other tiles changed location because the players had ventured into a tile I hadn’t actually prepared and I decided to steal something I had prepared for a different tile.

This actually came back to bite me once when I forgot to update my map that the tile had moved, and so from the players’ perspective, a particular location had suddenly ceased to exist, which they immediately noticed and were confused by. I did manage to come up with an in-world explanation for that, but it’s not a great player experience. To remedy this, I still think it’s a good idea to be somewhat flexible with where encounters may be placed, but to have a list of pre-prepared encounters per tile type that are interesting and engaging, so that I can pull them in when needed. When I eventually end up using one, I can lock it in.

Additionally, something I did naturally when thinking about populating tiles was to think about tiles as being locations, rather than encounters. So for example, rather than just having a grasslands tile where players could have a random encounter, I would add landmarks such as an orchard, a grove, a castle, or a cave formation. This not only served as milestones when navigating, but also allowed me to reuse areas so that players could revisit them, such as by expanding areas, destroying or significantly changing locations, adding new combat encounters by having monsters move in, or adding social encounters through wandering NPCs. In practice, I never made much use of this since players preferred to explore more of the map rather than revisit old locations.

While the Westmarches format states that players may stumble upon locations with encounters that are not appropriate for their level, in practice I didn't really do that and preferred to design encounters that were suitable to the levels of the characters engaging with that encounter. While this was more work, since I couldn't prepare encounters in advance and leave them for players to find, I think it made for a better player experience overall.

One remark I got from players when running the campaign this way was that the game felt very much like an open world. There was always something to do, somewhere to explore, adventures to be had, and plot hooks to complete. That made me happy, since that was the goal!

Planar Campaigns

Running a planar campaign meant that not only did I need to think about encounters for the overworld (or the Prime Material Plane), but also for any of the planes they happened to visit that were introduced through the campaign.

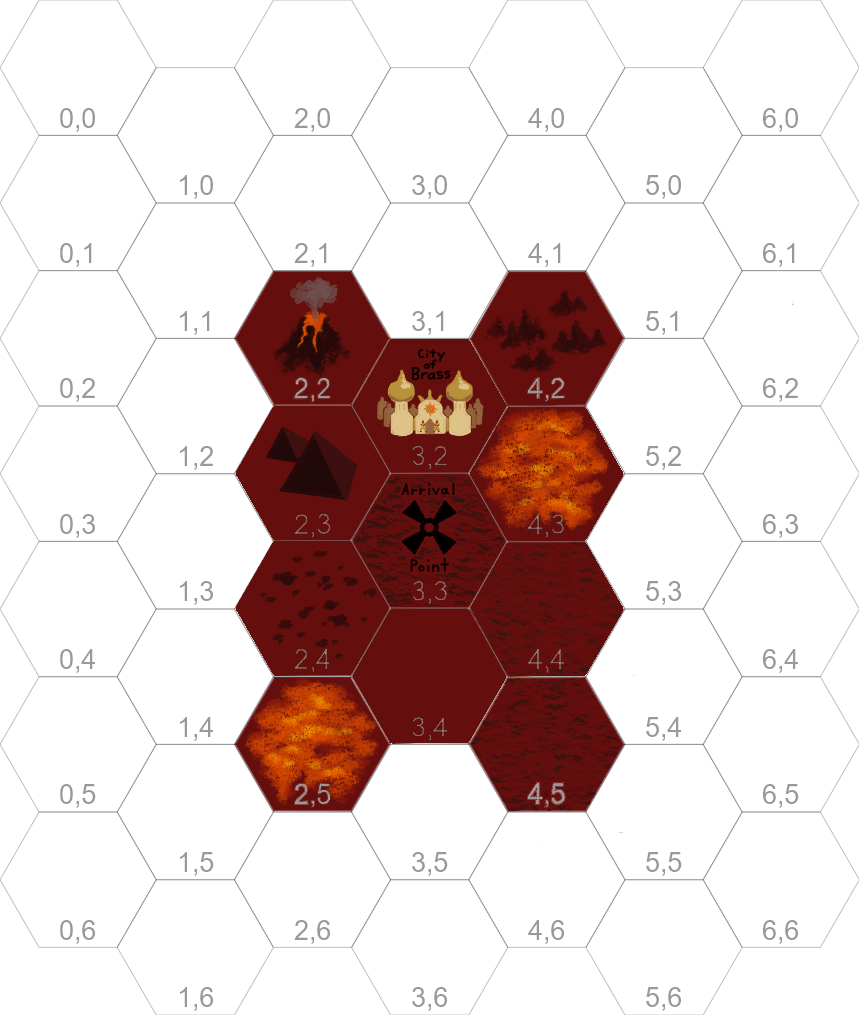

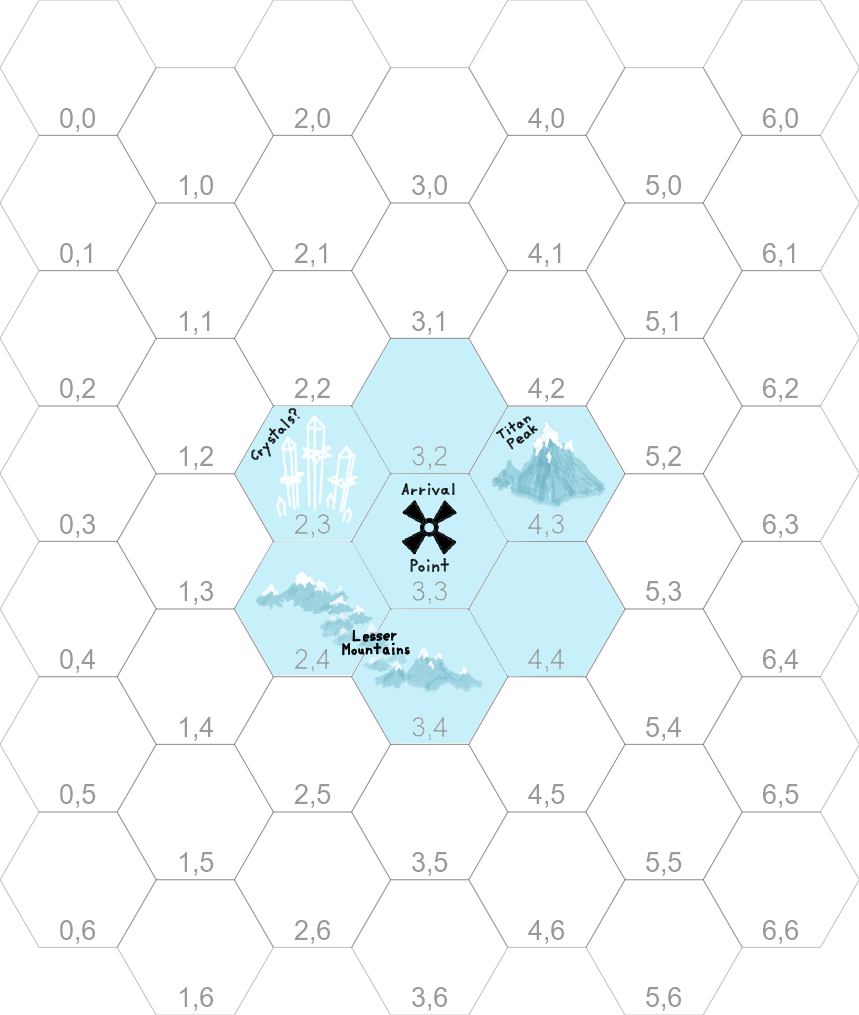

To reduce the chances that players would feel overwhelmed with amount of world to explore, planes were designed to be small compared to the Prime Material Plane, with maps being 6x6 tiles in size. I took inspiration from the multiverse described in the D&D 2nd Edition Planescape material, which included para-elemental and quasi-elemental planes, as well as custom planes that I made up (such as hinting at the existence of a Demi-Plane of Chess).

For plane specific encounters, inspiration was taken from material in D&D lore or third party material (such as people and places) when available, mixed in with inspiration from the real-world. Some planes had more depth to them than others (notably, the Plane of Fire is one of the more popular planes and has lots of material written for it, while the Plane of Dust has precisely 4 pages of material). This meant that sometimes time needed to be spent fleshing out these planes with suitable material on top of preparing for sessions, which took a lot of time.

Running a planar campaign also meant that I could take recognisable creatures and theme them slightly to make things fresh for experienced players and exciting for new players. One particular example was a wounded hill giant introduced to a party of level 1 players in the very first session of the campaign. By having the giant be affected by the Plane of Ice, I could give the creature the ability to sneeze hailstones, meaning the creature was now dangerous both in close combat as well as at range. This both kept players on their toes as well as sparked engagement with the premise of the campaign (giants don't normally sneeze hailstones, what's going on?)

Mixed Level Parties

Parties with mixed player levels is fun, and introduced a different dynamic to the game. Players with higher level characters were treated by players with lower level characters as having in-world experience and knowledge, and it was common to have a group of low level adventurers seeking protection from a character that was a few levels higher.

On the flip side, parties with wildly different player levels are incredibly tricky to balance for, especially with regards to combat encounters, and it doesn’t help that in D&D5E, level 1 characters are extremely fragile. To combat this, I attempted to devise combat encounters in such a way that skilled characters would take on stronger enemies, while weaker characters would take on minions or weaker enemies, and this approach seemed to work relatively well.

Modifying Campaign Rules

As the campaign progressed, I realised that I needed modify the rules somewhat.

The first rule I modified was character death. In the Westmarches, if a character dies, the player should make a new character at level 1. However, since I was using milestone leveling, this essentially meant that that players may have played for a significant amount of time only to have to redo their progress. I changed this rule so that on death, a player would only need to make a new character at the previous level.

The second rule I modified was about character progression. As some characters reached higher levels, and as some players left the campaign, I ended up with a party of high level players and a party of low level players, with both parties not really changing much. To encourage mixed parties, I added a rule that any player who was not at the highest level in the campaign would progress twice as fast. This allowed some low level players to catch up, and eventually even started adventuring with high level players.

Modifying Westmarches Rules

When I first explained to players how the Westmarches format would work, I largely stuck to the same rules described by Ben Robbins in his original writeup. However, sometimes breaking the rules worked out well!

The first rule I broke was one that stated that at the end of every session, all players should return to home base. The intention of this is simple; if players are meant to be able to change parties every session, it doesn’t make sense to do so when last session ended with one player’s character halfway up a mountain. However, I decided to break this rule due to upcoming summer vacations (so I knew I would end on a cliffhanger), and because I didn’t think this particular instance would throw a wrench in organising future sessions. The context: my players were exploring a desert when a fiery portal suddenly opened and two efreeti and several salamanders emerged. A battle ensued, and some characters were dragged through the portal, leaving them trapped on the Plane of Fire and unable to join parties on the Prime Material Plane until they found their way back. In practice, I ran separate sessions only for the characters that were abducted, organised in a private channel on Discord.

The other rule I broke was the home base being untouchable from foreign attacks (and not a place for adventures), with the idea here being that players are encouraged to seek adventure outside of the home base, and that they would always be safe when returning home. In this case, after a session where players uncovered some secrets about the ruling king, they were declared personae non gratae and a bounty was placed on their heads, forcing players to declare another location as their home base.

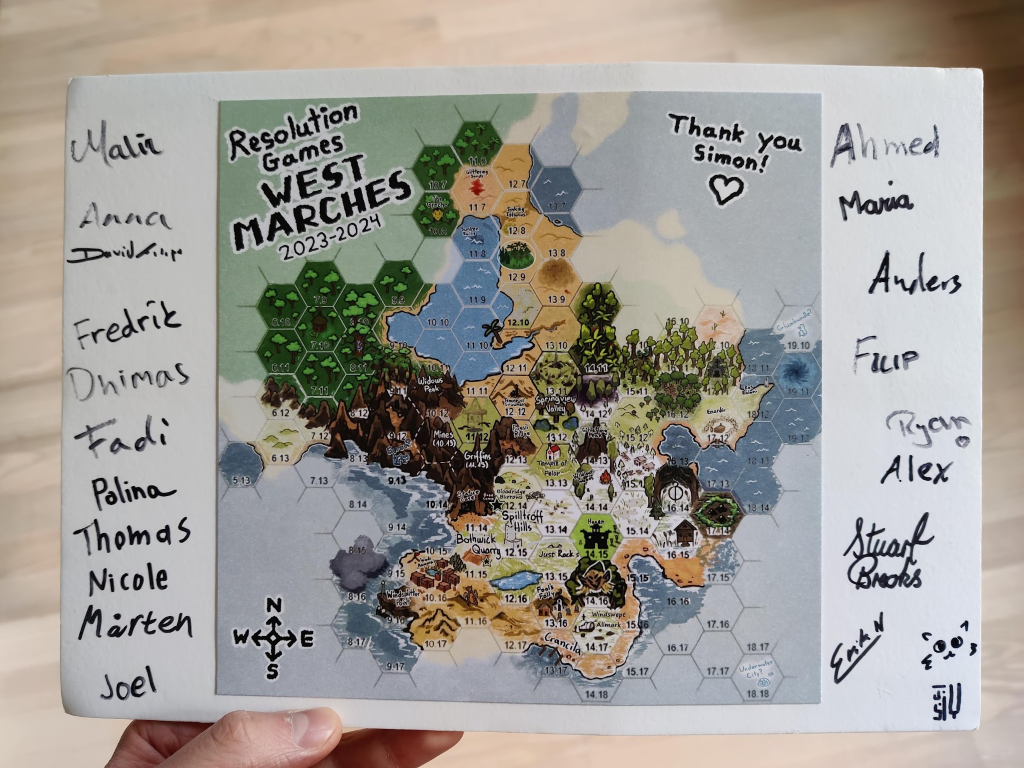

Player Contributions

Several players in the campaign tended to be very engaged and contributed heavily to making the game enjoyable for everyone involved. Especially when it came to writing up session notes and updating the shared map, there was always someone willing to jump in and take on the task. In particular, players managed to write 157 pages of session notes (just over 90000 words) for 36 sessions, which is impressive. On the flip side to this, the longer the campaign went on for, the harder I think it became for new players to easily jump in and figure out what happened in the game before they joined. If you also take into the consideration the history of messages on the Discord server, I can definitely see how new joiners might feel overwhelmed.

One of my favourite parts of running a D&D game with artists as players is that they bring their characters and the world to life through their art!

A Narrative Twist

While the Westmarches format places less emphasis on personal narrative and more emphasis on exploration, in practice I still tried to add some personal narrative hooks to the campaign, particularly for players who were particularly engaged with the campaign by roleplaying (and therefore had more to work with). This was done in various ways, such as dream sequences, portents, apparitions, and mysterious voices, all conveyed to the specific player through private message.

One particular favourite example is that of a player who was always invoking Avandra when rolling dice, so I incorporated that by having him experience an angelic visitation who bestowed upon him a personal quest in order to become a possible champion of Avandra.

Handout Overload

While running the Westmarches campaign, I realized that some tricks and techniques that I used when running a narrative campaign with a smaller group didn’t quite work with a larger group.

For example, I prefer medium to high magic games with lots of homebrew magic items. However, my predisposition to giving players magic items meant that there were suddenly lots of magic items in the party, and it become impossible to keep track of everything and to know who has what. I kept a list on hand of magic items I had made so that I could look up the effects, and once players acquired a Bag of Holding they also started keeping a list of communal magic items.

A similar issue I encountered was motivating players by using found objects in the world, such as diary excerpts, intercepted letters, map excerpts, and overheard conversations. The idea behind this was to provide additional adventure hooks outside of the provided list of rumours. In practice, this resulted in 13 individual handouts across 7 pages, making it difficult for players to keep track of things.

While I tended to give out printed handouts, printed item cards for custom magic items, and display images of locations and characters that players would encounter during their adventures, I didn’t even attempt to do this during a Westmarches campaign, simply because of the sheer amount of time it would take me to do something like that! For the sake of the entire group, I also preferred having things fully online rather than rely on physical handouts.

Conclusions

I hope this (rather long) retrospective blog post about my 2 year long Westmarches campaign gave you some ideas on how to run your own campaign or guides you to prevent making the same mistakes I did!

If you’re interested in learning more about the Westmarches format, I’ve linked some resources below. Good luck!

- Grand Experiments: West Marches, by Ben Robbins. These are the blog posts that popularized the Westmarches format.

- The West Marches | Runnning the Game, by Matthew Colville. A video aimed at dungeon masters about the Westmarches format.

- Hexcrawl, by Justin Alexander. These blog posts talk about running hexcrawl games, which Westmarches games use some elements of.

- Izirion's Enchiridion of the West Marches, by Dom Liotti and Sam Sorensen, published by The Goat's Head. This book is a great at providing tools for building a Westmarches game, and rules for running one.